Laura Verissimo de Posadas[1]⃰

Introduction

When words shiver and falter in the face of the blank page and in front of the obscure entanglement of thoughts, poets come to our rescue.

Without realizing it, I have followed Freud’s encouragement to resort to them.

Circe Maia (2007) comes to my mind with the verses that give this journey a title. Tatiana Oroño (2017), with her words, unveils to me one of my reasons for this attempt: “I write about what happened so that something happens to modify what is happening.”

We write in order to provide a time and a space for perplexity and impotence, in order to undo the maze of feelings and questions, that which stalks and urges for a destination other than repetition or discontent.

Sometimes, the starting point is a casual encounter or conversation that indicates a path towards writing; a route you follow not knowing either where it will lead you, or which geographies will be visited, or how arduous or enjoyable it can turn out to be. And much less, do you know which of your “belongings”, neither known nor thought about, will find letters for a first babble or will reach words, always precarious, always insufficient. The dilemma to face is whether to desert beforehand, to distract oneself – from what haunts us and from the anxiety that emerges – or to accept the risk.

What triggered this paper, its day’s residue, were five words “I did analysis with Helena [Besserman Vianna]”.

I think that only at the end of this text, will both the reader and myself be able to understand minimally some of the reasons for the impact these words had on me.

I had been familiar with the name Helena Besserman Vianna since the 70’s, when Latin-American countries were gradually falling under the control of military dictatorships that cooperated with each other in the sinister Plan Cóndor. I hold the picture of a solitary fighter, respected by many – accused and jeopardized by others – because of her courage during the Brazilian dictatorship (1964-1985); a military regime that violated the Constitution, as did the other Latin-American dictatorships, and substituted constitutional legality by “their own” legality, the Institutional Acts. It thus suppressed citizens’ rights and guarantees, and it persecuted, tortured and forced the disappearance of members of the opposition.

Those five words, heard in an atmosphere of affects and reencountered stories, awoke my wish to know what Helena was like in her clinical practice, what her listening was like, what her stance as an analyst was like. At the same time, it occurred to me that her “case” can shed light on the reflection about the – inevitable – interweaving between the analyst and her practice and the sociocultural environment where she exerts her practice.

I then set as an aim to explore both her commitment to the cause of the Human Rights and her commitment to the “cause” of psychoanalysis. It is not my intention to outline a biographical sketch, but rather, through the vicissitudes of her epic, to analyze current issues.

I am particularly interested in identifying contemporary features of social behaviours and, especially, the way in which analytic institutions and those of us who are their members are pervaded by those features in these post-truth times, with their narratives, their “liquid” forms of relating, the laxity of attitudes and practices – the evaluation of which seems to be restricted to the amount of success regardless of the means needed to achieve it – and the forms of exercising public responsibilities that we are witnessing today. As it seems impossible for us to remain immune, we should explore up to which extent these features can also mould analytic institutions. This concern has to do with the ethical dimension of our practice, both with our analysands and with our colleagues – and those who aspire to become one – as well as with the way in which we relate to our environment.

As we know, the salient features of any period of time are revealed by speech. Commonplaces and catch phrases in our language suggest – and lead to – the trivialization of conflict (“everything’s ok”, “you must forget about that”), as if the art of politics were the negation – necessarily untruthful – of conflict, and not the search for ways of overcoming conflict. They also promote the annulment of sorrow or the impact (“easy”, “nothing happens”) or strategies to dissolve responsibility (“getting it right or wrong”, “as I tell you this, I tell you that”).

So much so that, in its 2017 update, the Real Academia Española includes, among other new terms, the word posverdad (post-truth) (“Deliberate distortion of a reality, which manipulates beliefs and emotions in order to influence public opinion and social attitudes. ´Demagogues are masters in the art of post-truth´). It also includes the noun buenismo (goodness) (“Attitude expressed by somebody who, in the face of conflicts, reduces their severity, gives in with benevolence or acts with excessive tolerance”).

Not only have we become used to these expressions, but they also shape our thought and our action: not questioning, not reacting, seems to be the motto of political correctness. We are, thus, led into a loss of reflexes, and we are made passive by that discourse. Without realizing it, we resign ourselves to being efficient collaborators and accomplices, both by silencing something that has to be expressed in a loud voice and by the absence of reaction to procedures that bypass the rules that sustain the bond of the group, standards, the value of which resides in their regulating function and their “pacifying” effects of the inevitable tensions and conflicts that arise within any human grouping.

“Sometimes to remain silent is to lie”[1]

I said, at the beginning, that writing is to start a journey not knowing where it will take us.

In this case, I already had the main characters: Helena, as a modern Antigone; her psychoanalyst colleague (from a different association though), Leão Cabernite, training analyst of a doctor and psychoanalytic candidate, member of the torturing team of the Army, Amílcar Lobo; the latter belonged to the Sociedade Psicanalítica do Rio de Janeiro, SPRJ; Helena belonged to the Sociedade Brasileira de Psicanálise do Rio de Janeiro, SBPRJ and to the International Psychoanalytical Association, IPA.

However, I came across another woman, her voice rising from a thick weed of silence and oblivion. She was a German Jew, the daughter of the Freudian psychiatrist and socialist activist Dr. Heinrich Stern, who, after being arrested by the Gestapo and released a few days later, migrated to France with his wife and his daughter, Anne-Lise. They settled in Blois. When the Germans took Paris, they had to flee to the free zone, but, in 1942, with the occupation, Anne-Lise had to hide under a false identity, she was exposed as a Jew and was arrested on 1st April 1944. She was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and then transferred to other Nazi extermination camps, “that black hole, that anus

After the German capitulation, in the summer 1945, and back in France, she was received by the red cross in Lyon, when she was only 24 years of age. Her narration in “Time for cherries” (Stern, 2004, p. 301) is profoundly moving when she describes the reunion with her parents, whom she believed to be dead: “for us everybody was dead, so my parents as well […]. They were capable of listening to the horror, parents who were Freudian enough to be able to listen to everything, I mean everything, that I had to tell them” (p.113). They encouraged her to speak about the unspeakable and to write about it. Let us remember that in the post-war society – as gives testimony, among others, Primo Levi[3]‒ silence is what prevails. It wasn’t Anne-Lise’s experience when she returned:

Reemerging from that, from the camps, from having told them everything, has taken long years of psychoanalysis. But it is also this – and my chance in the camp itself, my relatively little deportation as regards the others – which made it possible for me to become an analyst despite / because of the camp. […] Not being able to talk about it because of not being listened to, that I knew much later, unfortunately, mostly in the psychoanalytic community (Stern, 2004, p. 113).

Anne-Lise Stern was a member of the so-called “third generation”, a condition she shared with, among others, Jean Laplanche and Serge Leclaire. This is the only reference to be found in the Dictionary of Psychoanalysis by Roudinesco and Plon in the entry devoted to Leclaire: there is no specific entry devoted to her. Lacan’s biography, by the same author, only includes two meagre comments in passing, even though Anne-Lise worked for years in hospital services directed by Jenny Aubry, she wrote papers on her clinical experience from the perspective of Lacan’s teachings – she was an analysand of his – and she took part in publications and debates that received broad dissemination by the press. In The battle of 100 years (Roudinesco, 1993), she is only mentioned as the person who had the initiative to gather together Daniel Cohn-Bendit and Lacan (p.81), because of her participation in the conference on psychoses organized by Maud Mannoni in 1967 (p. 113) and because of her questioning Althusser in one of the stormy meetings, in the early 80’s, subsequent to Lacan’s letter of dissolution of the Freudian School of Paris (EFP) (p. 269).

She is not mentioned in papers devoted to the horrors of the 20th century either. Her book, Le savoir-déporté (Stern, 2004), is not known by Latin-American psychoanalysts (personal communication) such as Maren and Marcelo Viñar, Daniel Gil and Mariano Horenstein, who have analysed the Shoah and its sequels in the West, although Anne-Lise herself was a victim and a witness of the extermination camps, and although Pierre Vidal-Naquet states that her texts reach “the peak in concentration camp literature”.

So much silence and forgetfulness around her intrigue me. How could we not discover her when reading Primo Levi, Semprún, Antelme…?

Her texts and her oral interventions in the congresses of L’École Freudienne de Paris bear the mark, says Catherine Millot (2004), of a double militant commitment. “Anne-Lise remembered, indefatigably, that the camps (as was said back then, before we started saying Shoah) occupied a central place in the discontent, not to say the unhappiness, of our time” (par. 2). Millot accepts that for a long time, she resisted Anne-Lise’s interpellation, and that she was not the only one:

Nobody listened to her […] As far as I am concerned, it was very difficult for me to listen to her. It exhausted me. The real is that which is impossible to bear, Lacan said. […] the insistence of a real that acquired the form of an obsession in Anne-Lise’s words (par. 3)

In 1979, in response to the offensive of denial of the crimes of the Nazi regime, whose main spokesperson in France was Robert Faurisson, Anne-Lise opens a seminar:

In 1979-1980 we have witnessed the holocaust deniers enter the public scene. The deported person I am immediately asked for help from my psychoanalyst colleagues. But they did not understand the urgency. Lacan was already leaving [she refers to his illness; he died in September 1981] and the others couldn’t see that a lock was about to be forced, an ethical lock. Now, we all know what that breach has gulped. (Stern, 2004, p. 109)

Anne-Lise considers that this seminar is a “public act, not only an acting out” (p. 265)

I stop at this concise formulation because it seems to be profoundly analytic and it condenses what I am trying to convey in this text: Anne-Lise, as a psychoanalyst, intervenes in the polis (“public act”), she creates a space where they can talk about “just what the community of psychoanalysts, as a whole, excludes” (p. 268), she carries out a task of “research-testimony” that appeals to the memory, both what is censored or omitted and also its uses and abuses. At the same time, and also as a psychoanalyst, she does not lose sight of the relation to the unconscious, with the drive and the expression in act of what, in herself, insists and “never ceases to not inscribe itself” (Lacan). To say “not only acting out” implies to legitimize this dimension and, at the same time, to rescue herself from the submission, so frequent among us, psychoanalysts, to psychopathologising the act[4].

Helena Besserman Vianna was also ordered to remain silent. Her book is entitled Nāo conte a ninguém… (Don’t tell anyone…) (1994).

In his text in homage to Horacio Echegoyen, René Major (2017) recalls the quality of being a “man of principles” held by the former president of the IPA (1995-1999).

In Anne-Lise’s terms, Echegoyen “forced the lock” of silence. In this case, a silence regarding serious ethical misconducts, both in the practice and in the transmission of psychoanalysis. Since the year 1973, it was precisely the silence from the institutions which constituted a refuge for the president of the Sociedade Psicanalítica do Rio de Janeiro, Leão Cabernite, and for Amílcar Lobo, training analyst and analysand, respectively. The analysand was, in turn, a member of a torturing team as a reserve officer from the Army. Helena is the person that, in this context of rupture of legality by the Brazilian dictatorship, has the courage to speak, to ask for help, facing the collective disavowal[5]. Her personal courage was not enough, an institutional bid was required in order to face the evil, which from the outside, from the State terrorism, had infiltrated the training of the analysts. But the institutional imperative (Calmon et al., 1999, p. 15) demands silence, “mystifying silence kept for almost a decade by the psychoanalytic societies of Rio de Janeiro and the IPA” (Besserman Vianna, 1994, p. 21).

The problem to discuss, both then and now, and that “should continue being discussed is the stance of the psychoanalytic societies regarding torture and dictatorship, so that, in the end, we can know why a psychoanalytic society submits itself to the irrational” (Besserman Vianna, 1994, p. 20). An issue that is always current and cannot be avoided by considering it a “fight among cariocas [6]”, as rightly indicates Miguel Calmon in the interview cited above (Calmon et al., 1999, p. 12).

On the contrary, it concerns us, it concerns every analyst and every psychoanalytic society. Returning to the “carioca case” is a form of promoting the analysis of the institution we belong to and of exploring and challenging collective defences.

One of these defences is the reciprocal exclusion between politics and psychoanalysis, which for Helena is “an everyday and schizophrenia-provoking double language” (Calmon et al., 1999, p. 15). In this way, they disqualify actions and texts that rescue psychoanalysis from the bubble in which they want to seclude it; as if this seclusion did not constitute, in itself, a political act.

Anne-Lise also suffers from the resource to exclusion when she seeks the “pass”, in L´école freudienne in 1971: a member of the jury supports his opposing vote by telling her that “they have heard her talk about politics, not about psychoanalysis”, as if her story as a woman and as a psychoanalyst could be separated from her story as a deported Jew, as if it could be cut away from that of her parents and from history.

Helena Besserman took serious risks and suffered humiliations from part of the societies that invoked the “cause” of the institution. That other resource, the excuse of their preservation, has a long story, as Roudinesco points out (2014/2015):

The policy of the alleged “salvage”, orchestrated by Jones and defended by Freud, was a complete failure that would lead, both in Germany and all over Europe, to an outright collaboration with the Nazi regime, but mostly to the dissolution of all Freudian institutions and the migration into the English-speaking world of almost all of their representatives. Had it not been implemented, the destiny of the Freudian ideas in Germany would not have changed in the least, but the honor of the IPA would have been preserved. And, above all, that disastrous attitude of neutrality, of non-commitment, of apolitical stance would not have re-emerged later under other dictatorships, like the ones in Brazil, in Argentina and in many other places in the world. (p. 414)

This prehistoric time – unknown to us as it may be – haunts us and arrests us. Even when the attempts against ethics blow up in our faces, the fear of being considered a moralist or a witch hunter paralyzes any reaction.

In normal times, it is not about the risk of personal or institutional integrity, but rather the fact that caring for the institution is, on occasions, the rationalization of the care for the feud, for the power of those who preach and exert such care by resorting to no matter what practices.

Whether it is one end or another, it justifies the means. Somebody assumes the position of an “illuminated superior” to whom the faculty of thinking is delegated, and the “ethics of the civil servant” (Gil, 1999, p. 11) are imposed, headless herds that “receive the line” are invalidated in their capacities for analysis and judgment of good and evil in each situation. A virtuality that is always present in the human tendency towards the “voluntary servitude”, brilliantly indicated by the young Etienne de la Boétie in 1576.

From the first groupings originating with Freud, a lucid Ferenczi (quoted by Roudinesco, 2014/2015) said:

I very well know the pathology of the associations and I know up to which extent can puerile megalomania, vanity, respect for empty formulas, blind obedience and personal interest reign in political, social and scientific groupings, instead of conscientious work devoted to the common good. (p. 138)

Another paralyzing force stems from the elaborations that are affected by such accesses of subtlety, such rhetorical arabesques – a kind of intellectual sybarite characteristic – that result in considering the issues of the polis from the heights of an aseptic arrogance.

The horrors of the century

Helena Besserman Vianna (Río de Janeiro, 1932 – Río de Janeiro, 2002)[7]

Anne-Lise Stern (Berlín, 1921 – París, 2013)

78765, psychoanalyst: thus signed Anne-Lise – without her name and with her deportation number – an article entitled “An SS slip of the tongue”, published in the Nouvel Observateur, on 3rd June 1969 (Stern, 2004, pp. 224-225).

These two women have much in common. They are both Jewish, which is enough for their respective family stories and their bodies to carry the marks of the hurricanes of History. Helena was persecuted, was the object of an attempt with a bomb under her car, and Anne-Lise had to face not only the person who set a bomb in a synagogue, in Paris (3rd October 1980), but also anti-Semitism, subtle and pertinacious, that leads the Prime Minister of the time to condemn the attempt that “wanted to hit on the Israelis that arrived at the synagogue and hit innocent French citizens who were crossing the street” (Stern, 2004, p. 315).

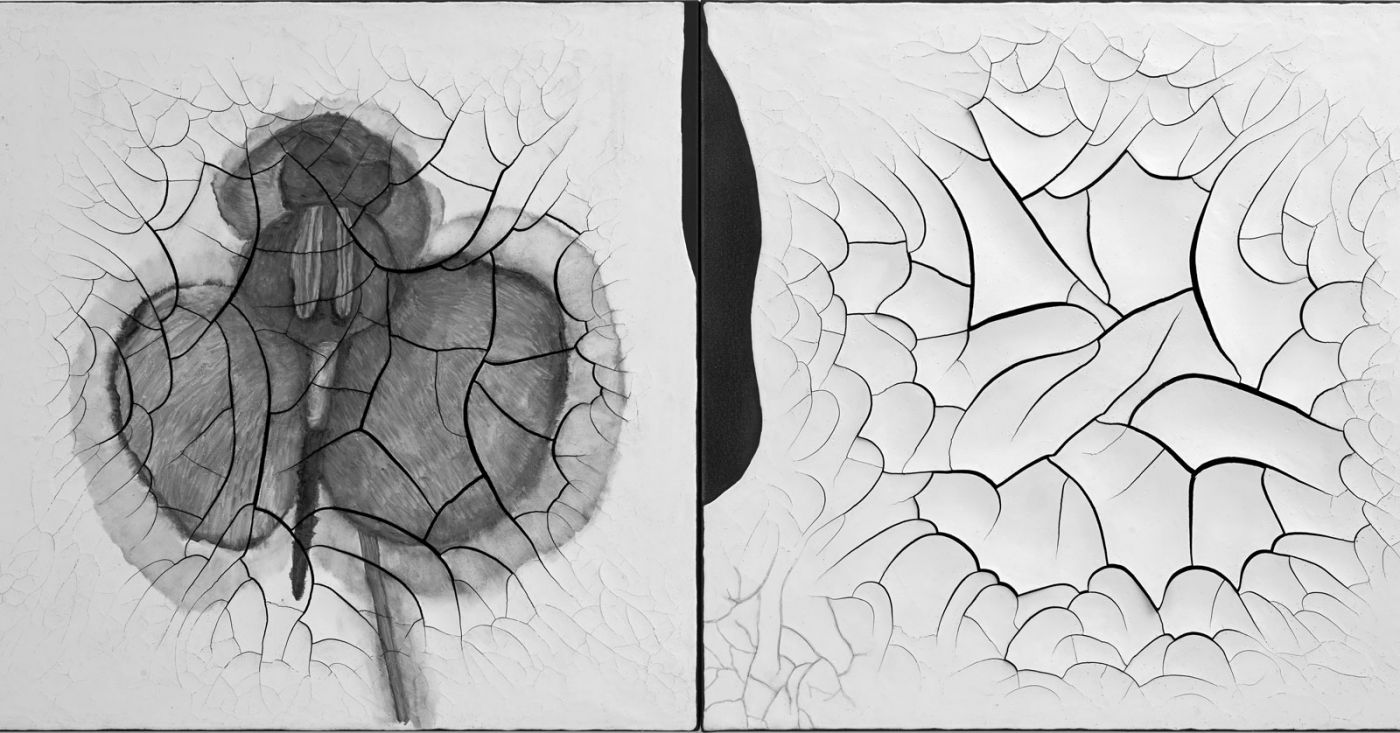

Out of their traces, tattoos, residues, are made women and psychoanalysts. They use their pieces so as to make a stained glass; “those stained glasses were not mere pieces of something smashed: they were her life, reconstructed very day, with new colors and textures”, the poet Adelia Prado (1989) could say about them.

They neither become alienated from them, nor do they disavow the reality in which they live. They both constitute their thinking as they become involved in action and they advance into the political scene, which, as is well known, suffers from masculine hegemony.

As Kristeva (2000) says about Hannah Arendt, we could say about Anne-Lise and Helena that “the anchorage in (their) personal experience and in the life of the century gives, in (their) texts, the impression of an action, an incision into the current world” (p. 43).

And, like Arendt, they exercise their thinking

at the heart of (their lives): in that specifically Arendtian feature we could be tempted into seeing a feminine singularity, to such extent it is certain that “the repression” that is said to be “problematic” in the woman prevents her from becoming isolated in the obsessive palaces of pure thinking and makes her drop anchor in the practice of the bodies and in the bonds with the others. (p. 22)

Catherine Millot (2004) underlines Anne-Lise’s womanly perspective in the day-to-day of the field:

What she brings to us is an unparalleled perspective, a perspective that does not turn away from anything, sustained by that curiosity she qualifies as Freudian because it is characterized by an attention that is free from prejudice, from pre-conceived ideas, which she, probably, owes to her parents – whom the preface of the book makes us come to know -, since the 20’s open to Freud’s discoveries. That curiosity, stronger than fear and hatred, is accompanied by an impressive absence of defensive withdrawal. Anne-Lise has, undoubtedly, drawn her force from her openness to the external world, from her free eye, her eyes excessively free, as she puts it […] Anne-Lise has also retained an eye open on the other in its sexed quality. The insistence on considering the other and herself as a man or a woman, is to grant him and grant herself a credit for humanity. Watching a German man and a German woman walking side by side as if they were lovers, she thought that they couldn’t be completely bad if they had, at least, desire for each other. (par. 8)

It brings me back Irene Nemirovski, who, while escaping Nazi persecution, can, in her fiction of the Suite Française, conceive of the romance between a French woman and a soldier of the German occupation army. It also brings back to me the analysts who propose a Plea for the humanity of the enemy (Viñar, 2006), appealing to a Mercy of Eros[8] (Gil, 1999).

In the text cited above, Viñar (2006) invites to problematize the position of the psychoanalyst in connection with the public sphere, with the complexities and volatilities of the sociocultural and political movements.

The most convenient position would be disregard, to say that psychoanalysis is not the competent and adequate instrument to explore the problem, to keep one’s mouth shut and move on to something else. However, in the sessions, this material about the horrors of the world is more and more present and it sometimes overflows. (p. 399)

Viñar (2006) finds himself “more concerned about how to ask the questions and enigmas than about the peremptory quality of the answers” (p. 403), which provides me with the words I need in order to define my project, since the present text follows Viñar’s path in terms of thinking of the analyst in a Moebius-strip-like topic: “the socially implied citizen and the subject of the unconscious” (p. 406).

In turn, Daniel Gil, in his Essay on the mentality of a torturer (1999), develops a research on the destructive potential of man. He wonders if “all human beings, under certain circumstances, behave in the same way, venting an aggression that is in their essence” (p. 8). As a psychoanalyst, he faces the difficulty of venturing, with our theories, into new fields that have been very little explored until now. He follows a philosophical route in order to approach fundamental concepts such as evil, ethics, morality, thinking (“thinking is the only activity that can protect men from doing evil”, p. 12) and, finally, he resorts to conceptual tools from Freud’s and Lacan’s theorizations so as to venture some hypotheses. From this deeply lucid and moving book – the reading of which I suggest – I would like to highlight the mercy of Eros, where Gil (1999) finds, as one of its exponents, Antelme, who

a little time after leaving Dachau, saved by a couple of friends who went there in order to save him, on the verge of death because of malnutrition and typhus, only barely recovered, finds out that in the allied prisoner camps German soldiers are being maltreated. He then raises his voice in protest filled with indignation with such treatment. (p. 114)

He concludes than an “ethical abyss” separates Antelme from the torturer who justifies his practice and from anyone who, one way or another, instrumentalises a human being.

I recently read in the press the statements form one of the greatest criminals in the trafficking in women: “I never stopped to think that the merchandise I imported were people like me. They were something else” (Jabois, 13th November 2017, par. 5).

Daniel Gil (1999), when returning to Freud’s theory in order to approach his subject, points out that we often forget the ethical dimension we can find in Freud’s thinking throughout his entire work (p. 111).

The ideals of the century

In these two women, this thinking exercised at the heart of their lives and in the bond with the others – in the words of Kristeva – is tributary to the teachings from their parents and their relationship with them.

As described earlier, Anne-Lise’s parents played a key role in her recovery form the trauma of Auschwitz. During their youth in Germany, Heinrich and Kathe had participated in the cultural atmosphere of the Weimar republic.

an atmosphere made of intellectual audacity and political commitment, wishing to understand and behave, with the shared conviction that Marx and Freud together would help to change the world, enjoying the pleasure, the discovery, of the freedom of the body and the spirit. (Fresco and Leibovici, 2004, p. 14)

Because of her family’s economic constraints, Kathe could not get a university degree, which she always regretted, but she always received, from the women in her environment, a militant spirit in favour of political emancipation and women’s causes. She enrolled as a nurse at the beginning of the 1914 war and there she met Heinrich. With the return of peace and expecting Anne-Lise, they settled in Manheim, where she kept the accounts of her husband’s medical consulting room. Self-educated and a passionate reader, she had social contact with intellectuals, artists, socialists and communists, whom she entertained in her living room during long and animated discussions while, at the other end of the apartment, Heinrich practiced general medicine and psychiatry. This atmosphere – luminous and broad-minded – was the one which reigned in Anne-Lise’s childhood. The choice of her name emerged from there, almost a homophone of analyse in French, which in her imaginary referred to the unconscious parental wish for that psy part that remains hidden.

As regards her own parents, Helena says:

It was the education my father gave me which led me into knowing, knowing much about the Talmudic histories. I think I know the way in which you discuss…every subject…[…] Feeling free to discuss things with my father and with my mother, but mostly with my father, with no need for any omissions or secrets, or difficulties to discuss any problem, that really opened me to psychoanalysis, where I expected to find the same situation. (Calmon et al., 1999, p. 29)

Impressive echo of Anne-Lise’s words! (p. 4) Helena adds a nuance:

Sometimes I found it, sometimes I didn’t. […] But I especially learnt from my father the question of responsibility and nominal responsibility. No responsibility can exist based on the assumption that we are all responsible because nobody is responsible in that case. The nomination of responsibility is a Talmudic question. If there is no name for the responsibility of any given act, the act is not taken into account. (p. 29)

Just as I randomly as I came across Anne-Lise, Helena – while she was investigating the history of psychoanalytic institutions – comes across Margareta Hilferding, the first woman who took part

It is in that atmosphere that was fervently contrary to any form of women’s emancipation or of their participation in intellectual activities that Margareta studies Medicine at the University of Vienna, bastion of the Austrian bourgeois conservatism. (Besserman Vianna, 1991, p. 32)

Women from the century of psychoanalysis

This “feminine specificity” that Kristeva talks about reveals something about the connection between women and words, the display of the body in the word as an act and in the act as a word: the enactment of the seminar, among others, in the case of Anne-Lise, and the enactment of the denunciation, in the case of Helena, are presences that leave traces in the political scene and, at the same time, evidence the imperative of saying and thinking about what is not said up to the very limits of the unspeakable. They both sustain a twofold opening to the real, to the external world and to the impossible, what Lacan describes as “that which never ceases not to write itself” and which real-izes (real-iza)[9] and emerges both in the theatre of the world and in their practices as psychoanalysts, both in their communication and questioning of their work with adults and children and in the hospital services and neighbourhood polyclinics.

In the spirit of May 68 – and funded by the money from the reparation the German government offered for her father’s consulting room -, Anne-Lise creates the Laboratoire de Psychanalyse (Psychoanalysis laboratory) in the area of the Bastille, where she offered psychoanalysis to those people whose economic conditions did not make it possible for them to have access to a psychoanalytic cure.

As

it is as if what I call the deported-knowledge – when it is time, it is time, a second later is too late – joined the creative function of the rush in the logic that finds expression in act such as is described by Lacan in Logical time and the assertion of anticipated certainty. (p. 187)

Another form of the vindication of doing, action, at the same time as it rescues the Greek notion of Kairos, the right time.

“Today is always still”[10]

A detailed description of the dimension of Anne-Lise’s and Helena’s practice as psychoanalysts, and their permanent commitment to the transmission of psychoanalysis exceeds the scope of the present paper. Reading them, discovering them, knowing the world in which they lived has been an exciting experience. They are two tireless thinkers who have enriched our reflection on issues that are both current and, simultaneously, timeless.

I will only refer to some aspects that are directly related to our position as analysts and are, at the same time, linked to debates we face as citizens of our country and the world, in these times of instant communications.

I have previously referred to the escalation of holocaust denial in France and to Anne-Lise’s reaction. The book by the denier Fourisson was prefaced by Noam Chomsky. In a letter to Jean Pierre Faye, Chomsky (cited by Stern, 2004) justifies himself: “We must defend the right to freely express different points of view, no matter how hateful they may be.” And he adds: “I see no reason for hiding my opinion, already publicly expressed, that the holocaust was the greatest explosion of mass insanity in the history of the human kind” (p. 158).

“Double standpoint”, says Anne-Lise. In the prologue to Faurisson’s book, under the title “Some elementary comments on the right to free speech”, Chomsky says:” I will say nothing, here, about Robert Faurisson’s work or about his criticisms, about which I do not know much, or about the subjects he deals with, on which I have no great enlightenment” (Chomsky, cited by Stern, 2004, p. 315). Striking clarifications coming from the prologist of the book! Hasn’t he read the author or the book he prefaces? His pretended ignorance does not prevent him from qualifying Faurisson as a “kind of relatively apolitical liberal”. Chomsky, thus, takes two stands: he acknowledges and condemns the Shoah and, at the same time, with his prologue of the book he legitimizes somebody who denies the horror of the gas chambers. The tools we intellectuals count with – even further in the case of somebody of his stature – are thus perverted: they are no longer used as an instrument for criticism, for revealing or denouncing the falsifications of history. Chomsky never retracted, but, on the contrary, he rather took offense from his French colleagues. Serious nominal responsibility – as Helena learns from the Talmud – given the influence Chomsky exerts on the world’s thinking scene.

Anne-Lise (Stern, 2004) accurately states that regarding the extermination of Jews as insanity or madness “evacuates the science involved: scientific extermination, based on “scientific” criteria for discrimination, for segregation” (p. 159).

Today, in 2018, this right to freedom of expression that we all defend does not relieve us form the necessary debate on its restraints in accordance with other rights and principles, a debate that is still open.

I recently read in the press that the chess champion Anna Muzychuk declined to participate in the world tournament to be held in Saudi Arabia. She wrote in Facebook: “In a few days I will lose my two world titles, one after the other. This will happen because I have decided not to go to Saudi Arabia. In order not to play by the rules of others, in order not to wear an abaya […] because I do not consider myself a second-class creature”. A lot of detractors jumped over her questioning that she had already participated in a tournament held in Iran, to which the Ukrainian player responded: “Iran was my first experience in a country with such oppressive laws over women. After having been there, I clearly realized how badly this situation made me feel. I am not devoted to politics and I do not intend to compare whether Iran or Saudi Arabia is worse. I have simply had enough”.

Less famous than Chomsky and without any refined intellectual elaborations, the chess champion teaches us a memorable lesson on ethics.

Helena, in turn, challenges the IPA, and not only the IPA, but also every psychoanalytic society, with her proposal not to give our backs to history itself, but rather to know it, to recognize it in its silences and disavowals. Facing our history, our deceits, our submissions and our miseries, doesn’t that constitute the heart of our task as psychoanalysts?

Wouldn’t this be the position to sustain in our practice in the institution to which we belong, framework for the transmission, so as not to slide down the slope of an anti-psychoanalytic attitude and in that way betray our foundations?

Helena argues against the idea that if you do politics, you leave the psychoanalytic field, since

some way or another, you do politics all the time. Politics does not mean politicking. But the most important form of politics would be to stop with omissions, to stop with secrets, to stop hiding important things, because this is what invigorates a power that the others are forced to conform to. (p. 13)

When she was asked what, in her opinion, determines the absence of reaction, the paralysis of the analysts, Helena strikes us with a powerful response: “Training”.

To remain subjugated, not to question […] neither the theory, nor criminal acts, sometimes. You don’t question. Why? Because it will denigrate the image of the psychoanalyst as that extraordinary subject who knows everything […]. And there, the question of filiation comes in, the subject who imitates. They are rare to find, I would even say very rare to find […], the psychoanalysts who have exercised as training analysts and whose candidates have achieved the freedom necessary to follow their own paths. (Calmon et al., 1999, p. 27)

If that were the case, the work needed to become an analyst would also remain paralyzed, work (Arbeit) in the Freudian sense, highly specific, made out of mournings and transferences that lead to the design of one’s own paths in the theory and the practice, and for which every group has to find and preserve the conditions of freedom that will make it possible. This has been the subject matter of the last meetings of the Institutes in FEPAL[11], which gave rise to the confrontation and interchange among the diverse psychoanalytic cultures of the Latin-American societies. The discussion focused on the so-called “didactic analysis”, point of concentration of power if the idealization of a “trainer” (didacta) who holds an all-embracing and flawless knowledge is preserved, the risk of unconscious pacts between analyst and analysand. Miguel Calmon (Calmon et al., 1999), in his already cited excellent interview, underlines that Helena has had the attitude of

confronting the subjects, the institutions, with the truths that these subjects and these institutions disavow, repress. […] Even if the institutions wanted to preserve themselves, I do not think they could know about themselves, the moment Helena made that interpretation, she makes it merge, she makes it appear. (p. 26)

This sustained analytical stance is what makes Helena, in spite of everything, wish to continue belonging to the IPA: “I think it is a place where I can say things and appeal for responsibilities” (p. 31).

In a partial review of the papers written by Helena (Besserman Vianna, 1973, 1979), we find an analyst who is rigorous in her work with the theory, of a mainly Anglo-Saxon filiation that does not disregard Freud’s work and which is permeated by philosophy and literature. We find a sharp clinician who is committed to her patients – whom we would call difficult today – who she analyses at a high frequency, at a rate of five sessions per week, cases she took with” patience and conviction” (Besserman Vianna,1976), providing body and words to intense transferential movements. In her writing, she manages to convey her personal form of thinking and interpreting.

Also in Anne-Lise we find a permanent theoretical work. Her teachers, her interlocutors – and occasionally co-authors – were such outstanding figures as Lacan and Pontalis, among others. Having studied Lacan’s work, she puts into play the orders (RSI) in the exploration of a child’s symptom. With theoretical subtlety, she proposes that “the terms Real, Imaginary and Symbolic have to be, always, understood as ´on the side of the Real´, ´on the side of the Imaginary´, ´on the side of the Symbolic´, as a pole, a direction, a facet, rather than as a domain strictly delimited” (Stern, 2004, p. 127). Her case reports are so original and gripping that Lacan followed them as if they were episodes.

The same look, insightful and challenging, she addressed to advertising and the media, that could, occasionally, trivialize psychoanalytic concepts.

fixated on the side of the Real. Or else captured on the side of the imaginary, they become demagogic feed for the masses thanks to the media. [She claims that] those two adventures are what has happened to Lacan’s concepts as he gradually created them. Thereof result all kinds of sliding, some of them heavy with consequences: his teachings have become mummified in fetish and hoisted as such. (Stern, 2004, p. 134)

As regards the way in which the Shoah is approached, she warns against the two slopes down which the subject can slide: “Auschwitz tends to be sexualized in order to avoid the unanalyzable, the inapprehensible of the gas chamber. There is also a tendency to “religionize” Auschwitz. My responsibility as an analyst, and as a deported person, is to fight against these two slopes” (Stern, 2004, p. 228). She refers to a picture taken by Bergen-Belsen of an emaciated man, with his arms crossed, surrounded by other corpses. The picture was published in a journal devoted to the Nazi atrocities against the Jews. That photo illustrates an article entitled “The Calvary of the priests”. In another publication, below the same photo, one can read: “Ecce Homo 45”. Outrageous misappropriation of the suffering of the Jewish people when it is reported in Christian terms and iconography (“Calvary”, “priests”, “Ecce homo”), even though the publication contains only documents on the death of Jewish people.

In 1986, C. Lanzmann breaks into the scene with Shoah. Just from the title, it opens to a new position, the idea of catastrophe substitutes the sense of sacrifice inherent to the word Holocaust. By concealing the images and, instead, making his interviewees talk, he breaks with the silence that Anne-Lise encountered time and time again. In line with his concerns, Lanzmann avoids the subjects of obscenity and jouissance. It is an artist, he who dares to deal with that impossible real of the camps and in this way he “sets memory into motion” (Fernández Rubio, 25th June 1988). Says Anne-Lise:

When Lanzmann presents his film in German-speaking countries, young people, after the screening of the film, assail him with their demands. It is because of him that they want to, it is because of him that they can finally say what there is in their hearts: to give testimony, they as well, of the absolute silence in their families whenever the words Jew or Nazi or gassed were pronounced (as for gassing, not even a word). In France as well, since the film was released, people started to talk, to dream about what, until that moment, had been excluded from the analytic work. (Stern, 2004, p. 243)

These two women represent two unique and powerful voices. We have given them the floor in these pages. I believe that in order that “something happens to modify what is happening” many “voices among voices supported” are needed, that make themselves heard with “patience and conviction”, as a form of love for that so elusive thing we call the truth.

Resumen

La autora se propone identificar los rasgos contemporáneos de comportamientos sociales y el modo como estos permean las instituciones analíticas y a quienes las integramos. Propone una reflexión sobre la dimensión ética de nuestra práctica, tanto con nuestros analizandos como con nuestros colegas ‒y los aspirantes a serlo‒, así como en nuestros modos de posicionarnos ante los avatares históricos.

A través de dos psicoanalistas, una brasileña (Helena Besseman Vianna) y una alemana deportada (Anne-Lise Stern), intenta profundizar en distintos aspectos del anudamiento entre lo singular y lo colectivo, lo institucional y el medio sociocultural y político.

Ambas mujeres constituyen un ejemplo paradigmático del impacto de los horrores del siglo XX, tanto el del nazismo como el de las dictaduras militares que asolaron Latinoamérica. A pesar de estos embates y las marcas que dejan en su condición de mujeres y de judías, el compromiso de ambas se expresa en su lucha por los derechos humanos, en su práctica como psicoanalistas y en su escritura.

Descriptores: Ética, Institución psicoanalítica, Mujer, Psicoanalista, Acto.

Abstract

The author’s purpose is to identify contemporary traits of social behaviour and the way in which they seep into psychoanalytical institutions and their members. The paper reflects on the ethical dimensions of our practice, both with our patients and with our colleagues ‒ and those who aspire to be one ‒ and also regarding the way we stand before historical facts.

It is through two women psychoanalysts ‒ a Brazilian one (Helena Besserman Vianna) and a German deportee (Anne-Lise Stern) – that the author goes deep into the relationship between the individual and the collective, the institutional and the social, cultural and political milieu.

Both women are a paradigmatic example of the impact of the twentieth century horror, both Nazism and the military dictatorships that ravaged Latin America. In spite of those blows and the wounds produced as a result of being women and Jews, the commitment of both of them finds expression so much in their fight for human´s rights as in their practice and their writing as psychoanalysts.

Keywords: Ethics, Psychoanalytic institution, Woman, Psychoanalyst, Act.

Referencias

Allouch, J. (1997). La etificación del psicoanálisis: Calamidad. Buenos Aires: Edelp.

Besserman Vianna, H. C. (1973). Uma peculiar forma de resistência ao tratamento psicanalítico. Trabajo presentado en el 28o Congreso Internacional de Psicoanálisis, París.

Besserman Vianna, H. C. (1974). A peculiar form of resistance to psychoanalytical treatment. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 55(3), 439-444.

Besserman Vianna, H. C. (1976). Considerações sobre a evolução de um tratamento psicanalítico. Trabajo presentado para candidatura a miembro titular de la Sociedade Brasileira de Psicanálise do Rio de Janeiro, Río de Janeiro.

Besserman Vianna, H. C. (1979). Três etapas de um tratamento. Trabajo presentado en reunión científica de la Sociedade Brasileira de Psicanálise do Rio de Janeiro, Río de Janeiro.

Besserman Vianna, H. C. (1991). As bases do amor materno. San Pablo: Escuta.

Besserman Vianna, H. C. (1994). Nāo conte a ninguém… Río de Janeiro: Imago.

Calmon, M., Junqueira, M. H., Ferreira da Costa, N. y Sério, N. (1999). Entrevista: Helena Besserman Vianna. Trieb, 7, 7-38.

Casas de Pereda, M. (1999). En el camino de la simbolización: Producción del sujeto psíquico. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Casas de Pereda, M. (2007). Sujeto en escena: El significante psicoanalítico. Montevideo: Isadora.

Etienne de la Boétie. (2007). Discurso de la servidumbre voluntaria, o el Contra uno. Madrid: Tecnos. (Trabajo original publicado en 1576).

Fernández Rubio, A. (25 junio de 1988). Claude Lanzmann presenta en España ‘Shoah’, película sobre los campos de exterminio nazis. El País. Disponible en: https://elpais.com/diario/1988/06/25/cultura/583192808_850215.html

Fresco, N. y Leibovici, M. (2004). Prólogo. En A.-L. Stern, Le savoir-deporté: Camps, histoire, psychanalyse. París: Seuil.

Gil, D. (1999). El capitán por su boca muere o la piedad de Eros: Ensayo sobre la mentalidad de un torturador. Montevideo: Trilce.

Horenstein, M. (2011). Lo que debe llevar el habla sin decirlo: Notas sobre la interpretación después de Auschwitz. Revista Uruguaya de Psicoanálisi, 113, 29-54.

Jabois, M. (13 de noviembre de 2017). Fui tratante de mujeres durante más de veinte años. Las compré y vendí como si fueran ganado. El País. Disponible en: https://politica.elpais.com/politica/2017/11/11/actualidad/1510423180_056582.html

Kristeva, J. (2000). El genio femenino: La vida, la locura, las palabras. Hannah Arendt (vol. 1). Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Lacan, J. (1985). Escritos 1. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI. (Trabajo original publicado en 1951).

Levi, P. (1995). La tregua. Barcelona: Muchnik.

Levi, P. (1998). Si esto es un hombre. Barcelona: Muchnik.

Levi, P. (2000). Los hundidos y los salvados. Barcelona: Muchnik.

Maia, C. (2007). Obra poética. Montevideo: Rebeca Linke.

Major, R. (2017). Un hombre de principios. Calibán, 15(1), 228-231.

Millot, C. (2004). Présentation du livre d’Anne-Lise Stern: Le savoir-déporté. Essaim, 13(2), 179-184.

Nemiroski, I. (2005). Suite francesa. Barcelona: Salamandra.

Oroño, T. (2017). Libro de horas. Montevideo: Estuario.

Prado, P. (1989). Cacos para um vitral. Río de Janeiro: Rocco.

Roudinesco, E. (1993). La batalla de cien años: Historia del psicoanálisis en Francia (vol. 3). Madrid: Fundamentos.

Roudinesco, E. (2015). Freud, en su tiempo y en el nuestro. Buenos Aires: Debate. (Trabajo original publicado en 2014).

Roudinesco, E. y Plon, M. (2005). Diccionario de psicoanálisis. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Semprún, J. (1963). Le grand voyage. París: Gallimard.

Semprún, J. (1995). La escritura o la vida. Barcelona: Tusquets. (Trabajo orginal publicado en 1994).

Stern, A.-L. (2004). Le savoir-deporté: Camps, histoire, psychanalyse. París: Seuil.

Viñar, M. (2006). Alegato por la humanidad del enemigo. Revista de la Asociación Psicoanalítica de Buenos Aires, 28(2), 399-416.

Viñar, M. (2016). La memoria del terror: Psicoanálisis-Shoa-tortura-desapariciones. Revista Uruguaya de Psicoanálisis, 123, 65-72.

Viñar, M. y

Viñar, M. (1993). Fracturas de memoria: Crónicas de una memoria por venir.

Montevideo: Trilce.

*This paper was awarded the Premio Psicoanálisis y Libertad by FEPAL.

[1] Miguel de Unamuno.

[2] “ce trou noir, cet anus mundi” (personal translations from French and Portuguese in every case).

[3] Only in 1963, after the publication of his second book, The Truce, Primo Levi reaches a broad audience, as well as recognition for his first book, written in 1945.

[4] This seminar, offered during 30 years under the title “Camps, history, psychoanalysis: their ties with European current life”, will be recognized in 1992 by the Maison des sciences de l´homme.

[5] The Clínica da familia (Family clinic) in Rio das Pedras, in Río de Janeiro, bears the name of Helena as a tribute for her struggle in favour of ethics in psychoanalysis and for her participation, together with her husband, Dr. Luiz Guillerme Vianna, in movements against the military regime. Because of her commitment to the re-democratization of Brazil, Helena received the Medal Chico Mendes.

[6] Inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro.

[7] The daughter of Polish Jews who emigrated to Brazil in the mid-twenties. She initially lived in the area where the poor Jewish population was concentrated. She was dismissed from her public position as a pediatrician by the military regime in 1964.

[8] In this study of captain Tróccoli ‒ self-defined “professional of violence” who admits having tortured ‒, Gil (1999) recovers the original Latin meaning of the word mercy: compassion for the suffering, the misfortune of the other (p. 10).

[9] I use a term from Myrta Casas de Pereda.

Note from the translator: iza as in the Spanish izar una bandera, raise a flag.

[10] Antonio Machado.

[11] Organized by the Committee for Training and Transmission of Psychoanalysis of FEPAL, coordinated by M. Cristina Fulco (2014-2017).